While the genesis of the LongPen® originated in publishing (see history below) and the LongPen® for publishing completed over 50 high profile signing events with authors such as Dean Koontz, Norman Mailer and futurist Ray Kurzweil, adoption in publishing was limited.

In 2007, a branch of the Ontario Government reached out to Unotchit (now Syngrafii iinked) as they required physical documents signed in ink from Ministers located all over the province. Syngrafii solved the need of the government, and it was this breakthrough into business and government applications that allowed the company to develop and eventually unveil an advanced eSignature and Video Signing Room platform with 11 patent families and over 45 granted patents in the space. The iinked Sign™ Platform is widely used globally in government, finance, logistics, C-Suite, court documents, law firms, and financial contracts.

The security the LongPen® offers, with the signor being required to physically apply their one time use original signature in real time on documents has also allowed the company to start to displace the Autopen – a device that stores signatures and allows anyone with access to the device to apply signatures of anyone at will, without their permission.

The LongPen® Desktop Business Writer

History of the Invention

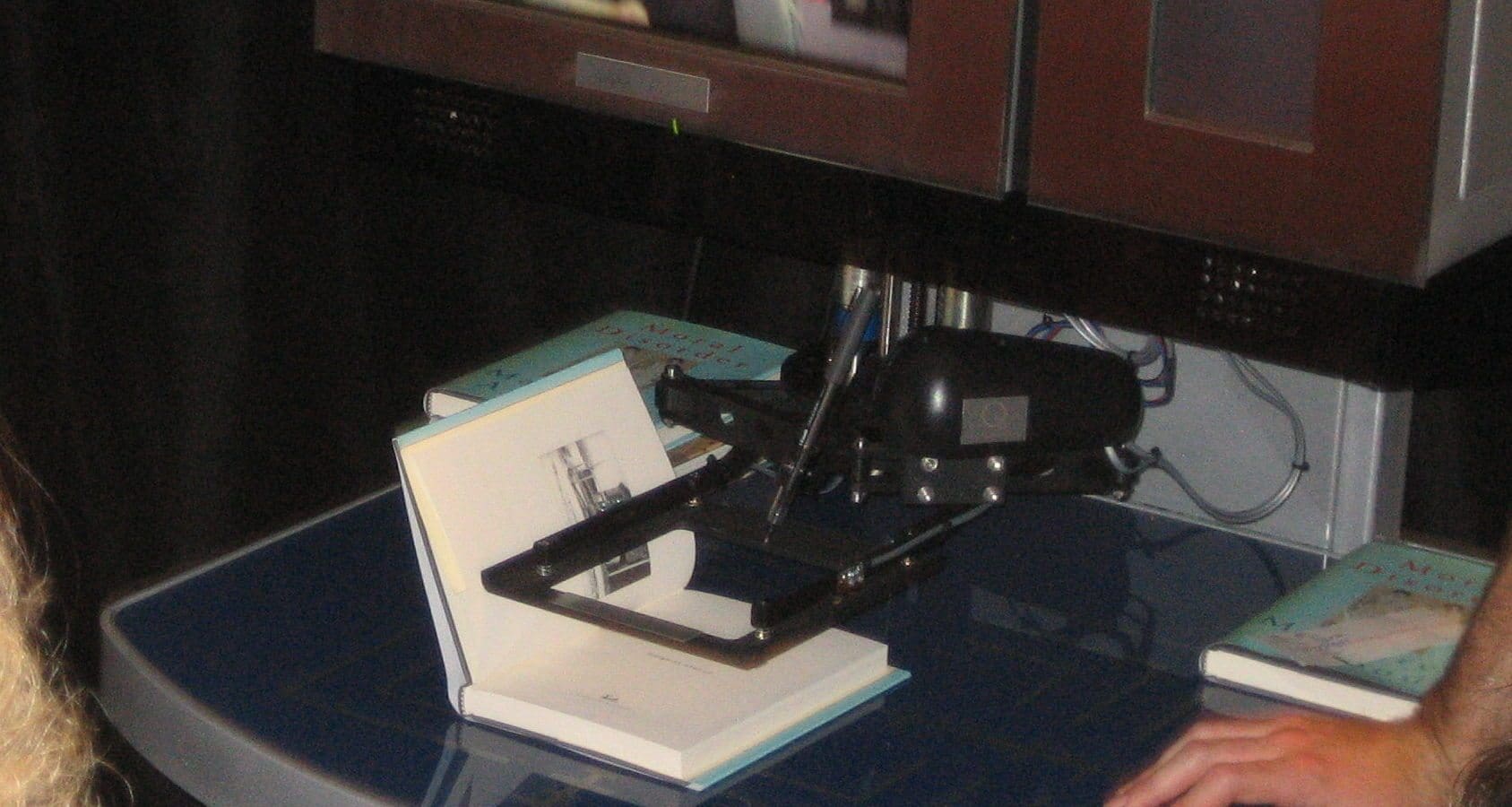

Author Margaret Atwood had a concept for a remote signing device that would permit authors to have high-quality video conversations with remote readers and provide them with a personalized copy of their books as if the meeting had taken place in person. The advantages of such a service were many. The reduced carbon footprint associated with travel; reaching readers in markets where book tours might not often get to; a digital memento of the meeting; and finally, a personalized copy of their book in the author’s own handwriting.

Challenge

Translating complex movements proves difficult

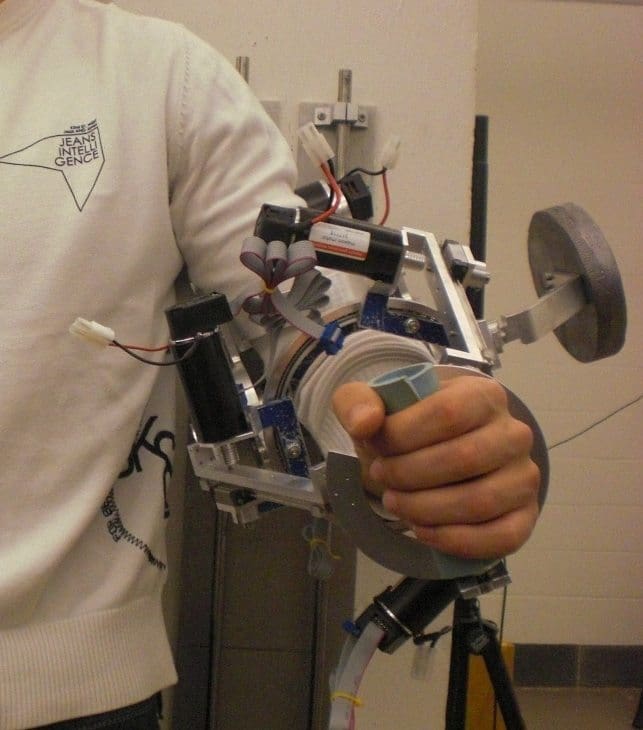

With her first vision of the LongPen Freehand Script Robot in mind, Atwood teamed up with Matthew Gibson and formed Unotchit Inc.¹ (pronounced “you no touch it”) in 2004 that in 2013 rebranded as Syngrafii iinked™. The company began experimenting with ways to bring the idea to reality, which proved to be more complicated and challenging than anticipated. Why? The apparent ease with which humans move their hands to perform such deceptively simple tasks as signing a book is actually powered by complex movements that use 40 per cent of the brain’s capacity. To replicate these movements requires the ability to precisely control the angle of joints and the pressure of fingertips on a hand that oscillates at 30 Hz and pulls at 6 to 9 G’s across space. “We [initially] underestimated the technical difficulty in replicating what nature has taken a great deal of time to perfect,” Gibson told Design Engineering magazine. With no clear path to proceed along, development of the LongPen system came to a standstill.

Solution

Advanced control schemes for rapid control prototyping and development

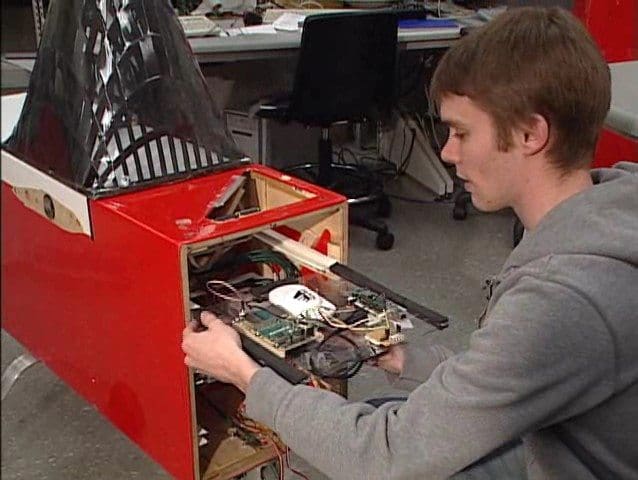

By chance, the breakthrough came in 2006 when staff at Quanser came across an article about the then-theoretical LongPen. Seeing the newspaper photo, Quanser’s technical experts’ – with decades of mechatronics innovation experience – were able to discern that the mechanism could not work as it was, and they immediately knew how to solve the problem. A phone call was made and Quanser explained to Gibson that, as a leader in designing and developing specialized, real-time control systems for academia, government and industry, Quanser’s team had the expertise that Unotchit needed.

Quanser used its rapid control prototyping and hardware-in-the-loop testing software, WinCon*, to examine the mechanical design and resulting dynamic equations. WinCon converts Simulink® graphical control blocks into real-time code which simultaneously sends and receives command and measurement signals to the LongPen robot via Quanser’s unique controls hardware infrastructure. Quanser’s advanced control schemes allowed Unotchit to keep the robot’s motor small. Without those methods, mimicking complex hand movements would have required a powerful motor and resulted in an extremely bulky device.

Result

From a proof-of-concept to the first transatlantic book signing in just a few months

Quanser’s advanced and innovative mechatronics development team was able to create a proof of concept in just three days. Gibson was impressed with the way in which Quanser built on Unotchit’s initial designs. “They took all of that work, extrapolated and built it into a rotary control instead of linear control – and made it smaller and faster,” Gibson told Design Engineering magazine.

By drawing upon its own in-house expertise and technology, Quanser was able to develop the initial proof-of-concept prototype into a final, tested design for production and then take it to full manufacturing within only a few months. “The speed, accuracy and repeatability are incredible,” says Gibson. “To accomplish this in such a short timeframe is remarkable.”

Equally important to Unotchit, Quanser was able to work with the company in a way that respected its intellectual property concerns. Working with leading Toronto IP law firm Bereskin & Parr, Quanser was able to draft an agreement that allowed Unotchit to retain control of LongPen’s IP.

On September 24, 2006, when the first transatlantic signing took place from Toronto, Atwood was able to realize her dream. Now, thanks to advanced robotic technology, Atwood and other authors can autograph books for fans on the other side of the world using a tablet PC and an Internet connection. A Unotchit robot, brought to life by Quanser’s innovative technology, signs the books on the other end. Margaret Atwood is now trading in multi-day, multi-city book-signing tours for the comfort of her own home.